Ever wondered why there is such intense disagreement over the evolutionary significance of development, non-genetic forms of inheritance, and niche construction? If so, you may be helped by a recent analysis by Tobias and Heikki Helanterä. The paper, accepted in the premier philosophy of science journal British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, uses niche construction as a case study to demonstrate how the way we think of causality in biological systems shape the structure of evolutionary explanations.

Richard Lewontin famously described evolution by natural selection in terms of three principles: variation, differential fitness and inheritance. Organisms fulfil these principles and so they evolve, diversify and adapt. But this does not tell us how the principles are causally related, nor how they should best be construed.

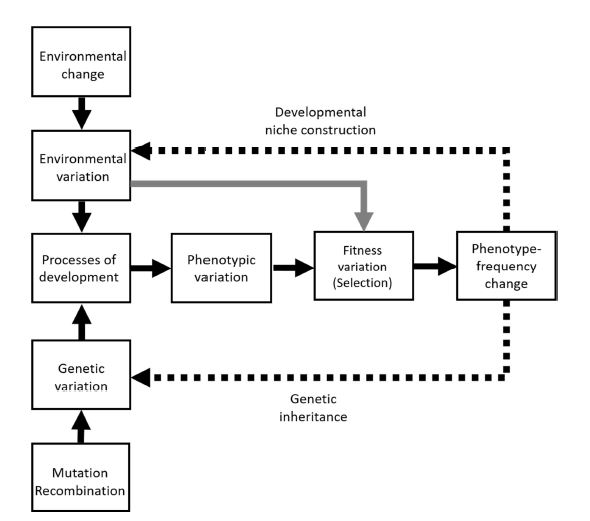

The classic instantiation of Lewontin’s principle describes evolution in genetic terms. This version is what we are taught at school. What we are not often taught, however, is that the genetic instantiation imposes a large degree of autonomy on the biological processes that produce variation, differential fitness, and heredity. Variable rates of survival determine what features will occur in the next generation. But selection does not affect the process of inheritance; inheritance is merely the passing on of whatever genes were selected. The variation that fuels evolution is similarly autonomous. Mutations occur randomly with respect to their consequences for development and fitness, and the acquisition of new variants does not change how variation is transmitted down generations. The result is an ordered set of causally autonomous processes; each step determines (partly) the inputs for the next step, but not how those inputs will be processed.

The autonomy of variation, differential fitness and inheritance is deeply entrenched in contemporary evolutionary biology. But it is a convenient heuristic and not a logical necessity, and it may or may not accurately capture biological reality. Many biologists suspect that it does not and that, in the real world, causes of variation, fitness, and heredity are intertwined. Tobias and Heikki show that such alternative instantiations of the principles of evolution by natural selection can affect the structure of evolutionary theory. And this, in turn, can make it perfectly valid to consider both natural selection and niche construction part of an evolutionary explanation for why organisms are well suited to their environments.

Failing to appreciate how different instantiations of Lewontin’s principles affect causal explanation in evolution is a major source of communication failure surrounding not only niche construction, but also developmental plasticity, extra-genetic inheritance and other phenomena.

Tobias and Heikki also suggests another reason people do not seem to understand each other: the views held by scientists on how science works. Many scientists expect their deep-held views, such as the core of the genetic instantiation of evolution by natural selection, to be falsified by data before they consider alternatives. Other scientists put less emphasis on anomalies and evaluate conceptual frameworks primarily on their ability to stimulate useful research. These different perspectives on scientific progress cut across disciplines but are rarely made explicit in scientific debates.

Nevertheless, philosophy of science is important to understand what the contention actually is about. If one considers niche construction theory an attempt to formulate an alternative research programme, it should be evaluated on the basis of its ability to stimulate new questions and predict patterns and phenomena that would otherwise appear surprising; not on the basis of whether or not it falsifies the genetic perspective. On the other hand, those arguing for more substantial conceptual change must strive towards showing that their framework leads to a different, theoretically and empirically progressive, research programme. Maybe the need for scientific pluralism is a good topic to bring up at your next coffee break?