Highlights from ESEB 2017

This year’s European Society for Evolutionary Biology meeting was held in Groningen. ESEB is always a great opportunity to see old friends, learn new things, and – somewhat jealously! – see the progress on the most famous study systems in evolutionary biology, such as cichlids, Heliconius butterflies, and bird beaks. And progress there was. Among the most memorable were further evidence from the Seehausen group – presented by Joana Meier and others – that hybridization has played a creative role in fish evolution in both African and European lakes, and a tour-de force of Heliconius evolutionary genomics in a plenary by Chris Jiggins (there is a book, not only for butterfly lovers!). Hybridization was hot at the meeting so it was a shame that Yang was unable to join this year. Wallies were represented, however, by a nice talk on the ventral colour polymorphism by Pedro Andrade. Chances are they will make a big splash next year in Montpellier!

To be fair, ESEB has never been a hotspot for development and this year was no different. Manhattan plots abound, but there was generally little process-oriented research to allow us to connect genotype and phenotype. Exceptions included an excellent plenary by Renee Duckworth, where she demonstrated how to integrate proximate and ultimate causation to understand why organisms change over time or, in this case, why they may not do so. Another exceptional talk was delivered by Alex Badyaev, expanding on his recent papers on the evolution of carotenoid colouration in birds. Describing evolution as transitions between external and internal control in regulatory networks, this work demonstrated the potential for taking a comparative network approach to study innovation and diversification from a developmental perspective.

Other welcome islands in the sea of genomics of adaptation include Andreas Wagner’s plenary on innovation and modularity, or a talk by Christoph Thies from Richard Watson’s group who presented some refreshing ideas on evolutionary transitions in individuality and demonstrated how to capture this process formally. Plasticity and evolution was represented here and there, including an update on the spadefoot toad story by Ivan Gomez-Mestre.

Judging from the ESEB talks, evolutionary biologists are very interested in extra-genetic inheritance. Most talks – including a pretty well-attended symposium keynote by Tobias – revealed this interest to largely be about adaptive function, but with some nice links to life history and ageing (many thanks to Foteini Spagopolou and the other organisers). With a better integration between development and evolution we may look forward to more work on how inheritance systems actually originate and evolve. Chances are Daphnia will deliver some of the pieces of the puzzle and Reinder’s poster – showing preliminary data that quantify the extent of extra-genetic inheritance – was indeed well attended.

The poster sessions were actually one of the meeting’s highlight. Taking place in what resembled an aircraft hangar, it was cool and spacious. And there was wine. Nathalie – presenting her work on the evolution of embryonic gene expression in wall lizards adapting to cool climate – was super busy explaining her findings to other attendees. The whole meeting was full on – I did not even manage to talk to many of the people I know well!

It is always nice to visit Groningen, a place where many of the most creative researchers in evolutionary biology took their first steps as MSc students. With 1600 attendees, these meetings are really too big to take on, but the organising committee – headed by Leo Beukeboom and Simon Verhulst – did a great job pulling it all together. We are already looking forward to see what Turku and Prague can come up with in the years to come!

Read More

Friends shape the distribution of genetic variation

Small encounters can have large impacts. This counts for animals as well. Particular for social animals – such as great tits – encounters with others affect how they move around and where they eventually settle. And this influences with whom they mate and how successful they are in life. In a new paper published in Molecular Ecology, Reinder Radersma and colleagues from Oxford and Sheffield show that the social environment has a large impact on the movement of great tits – a bird species roaming around Wytham Woods and many other Eurasian forests. These movements affect the distribution of genotypes, which is crucial for how the population can evolve. After all, the distribution of genotypes across an area shapes the genetic combinations that arise and thus, the opportunity for local adaptation.

A particular difficulty when investigating how movements are affected by social interactions is that it is very hard to separate social effects from other factors which vary in space. For instance, when food is not equally distributed – as is often the case – animals might aggregate in food-rich areas. It may look like individuals choose to interact, because many individuals are at the same location. However, it is simply the food, not the company, that is the attraction.

Reinder and his colleagues used techniques recently developed for spatial statistics and extended its use to analyze social networks to separate the effects of spatial variables and social interactions on tit movement.

They show that the movement of individuals and therefore the distribution of genotypes is strongly affected by the preference to move around with the same individuals, in other words, hanging out with “friends”. In addition, the birds do not befriend simply individuals that live in close proximity, because neighbors have similar genotypes. Instead, they pick friends that are genetically different from themselves. As a result, the genetic structure of the population is affected by both social and spatial effects.

Read More

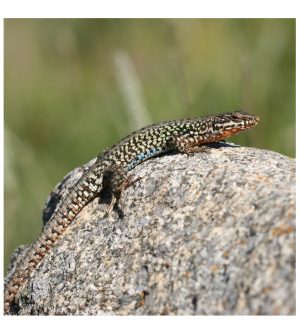

Why do lizards smell?

Many male lizards produce secretions that they rub on the ground of their territories. The function of these secretions remains contentious, in particular whether or not they serve as indicators of male fighting ability or suitability as a mate. A new paper, published in Evolution, suggests that sexual selection on chemical composition is, in fact, quite weak.

Headed by recent PhD graduate Hannah MacGregor, and in collaboration with Geoff While and Patrizia d’Ettorre, we analysed the chemical composition of secretions from male lizards from France and Italy. The results confirmed previous work showing that chemical profiles can correlate with male secondary sexual characters. However, the correlations were generally weak and inconsistent across the season and between populations. More importantly, there was little evidence that a male’s chemicals make him have more offspring.

That sexual selection on the femoral secretions is weak was further supported by the overall neutral pattern of introgression of chemical profiles in the hybrid zone between the highly sexually selected form (the ‘Tuscan’ lizards) and the ancestral phenotype (details on this hybrid zone can be found here). Nevertheless, three candidate compounds were candidates for asymmetric introgression via direct selection or genetic linkage with visual or behavioural characters.

On the whole, these results are bad news for the hypothesis that chemical communication is sexually selected in wall lizards. Instead, femoral secretions probably function as signature mixtures; that is, they help lizards to keep track of who’s who and to resolve territorial disputes. Yet, every now and then, a particular compound may become consistently selected – perhaps due to genetic linkage – and evolve a more signal-like function. May we speculate that this process can be facilitated by introgressive hybridization?

Read More