Geoff While visiting

We are very happy to have Geoff While from the University of Tasmania visiting us for three months. Geoff is a fantastic friend and collaborator whose scientific drive, passion for biology, and lizard catching skills are nearly impossible to beat. In addition to the usual wall lizard field season, we have a few old projects to finish off, some that are in full swing, and perhaps one or two new ones to launch. Not to mention all the other things you could get done over a beer or two. Welcome Geoff!

Cheers!

Cheers!

Read More

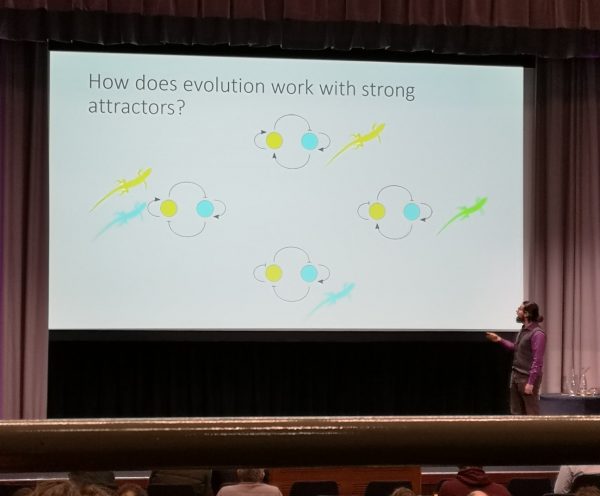

Ullergroup at Evolution Evolving

The Evolution Evolving at Cambridge was packed with three days of exciting talks – from culture in whales to control theory and the philosophy of explanation. The crew from Lund felt like lizards in the sun – pretty comfy and happy! So much in fact that Alfredo won the prize for best talk, and Illiam the prize for best poster. Congratulations to both!

We are very grateful to our fellow organisers and all the participants for making this such a great event. A full conference report will be posted in due time at the EES webpage, together with recordings of plenaries and key notes. They were brilliant! Until then, you can see what you missed at #evoevolving and #EES_Update

Alfredo on “How does evolution work with strong attractors?”

Read More

How adaptive plasticity evolves when selected against

Yes, that is the surprise title of Alfredo’s new paper in PLoS Computation Biology! When we discover examples of adaptive plasticity we usually think that it evolved because selection favoured it. But can adaptive plasticity evolve when selection favours non-plastic individuals?

Think of a population of insects that hatches, reproduces and dies twice every year: once in spring and once in autumn. Spring and autumn conditions may be very different, but plasticity could allow the insects to cope with both seasons. Yet, insects born in spring never experience autumn, and vice versa, so natural selection cannot directly favour plasticity. In fact, plastic individuals may do worse than individuals that are not plastic, which means plasticity could consistently be selected against.

This problem is similar to tuning the learning rate in Machine Learning. To teach a machine how to solve a problem, we give it a set of example questions we already know the answer to. Each time the machine gives us the wrong answer, we change its parameters to produce a new answer that is closer to the right one. If the examples share a consistent logic, the machine will eventually find this logic. But if we change the model’s parameters too much with every example shown, the machine will just repeat the solution for the last example, which prevents it from finding the underlying logic that connects the examples.

Just like in machine learning, organisms receive a set of questions in the form of environmental cues and need to provide the right answer in terms of a fit phenotype. Adaptive plasticity is the solution that produces the right phenotype for every environment. Organisms that see only one environment per lifetime could easily “forget” that plasticity is adaptive and instead only produce the right phenotype for their last environment. The offspring of insects that live in spring would be better matched to spring, even though they will have to deal with autumn conditions.

So when does learning theory predict that a machine will learn the logic of plasticity rather than the last solution? And do those predictions hold for a simple representation of evolution by natural selection? To find out, have a look at the paper!

Read MoreSolved: the genetics of colour polymorphism in wall lizards

A new paper in PNAS reveals that the orange and yellow ventral colour morphs in wall lizards is caused by regulatory changes in pterin and carotenoid genes. Interestingly, it seems like the alleles are old and occasionally shared between species. Miguel Carneiro and his team at CIBIO and Leif Andersson at Uppsala led the work, and we helped with the genome, samples, and other bits and pieces. The chromosome-scale genome assembly is of high quality and should become a useful resource – so just get in touch if you want to know if the wallies are right for you too!

A new paper in PNAS reveals that the orange and yellow ventral colour morphs in wall lizards is caused by regulatory changes in pterin and carotenoid genes. Interestingly, it seems like the alleles are old and occasionally shared between species. Miguel Carneiro and his team at CIBIO and Leif Andersson at Uppsala led the work, and we helped with the genome, samples, and other bits and pieces. The chromosome-scale genome assembly is of high quality and should become a useful resource – so just get in touch if you want to know if the wallies are right for you too!

Read More

A new take on the epigenetic signatures of prenatal stress

The conditions encountered in the womb can have life-long impact on health. It is usually assumed that this is because embryos respond to adverse conditions by programming their gene expression. In collaboration with Bas Heijmans and others, we propose that these effects also can be caused by selection on stochastic epigenetic variation. The paper is published in Cell Reports and there is also a press release.

The concept of fetal programming is based on the idea that embryos modify their physiology in response to the uterine environment. This may be good if conditions stay as predicted. But it may have negative health effects later in life if the conditions change. The concept of programming has been backed up by associations between adverse prenatal conditions and patterns of DNA methylation – an epigenetic mark that regulates gene expression.

Our simple insight is that the uterine environment does not need to induce changes in DNA methylation for this association between adverse prenatal conditions and DNA methylation to arise. In the early embryo, stochastic differences in gene expression can become stabilized by DNA methylation, resulting in embryos with different epigenomic profiles. Not programmed by the environment, these random differences in gene expression (and hence DNA methylation) may nevertheless provide some embryos with a survival advantage when conditions are harsh. In other words, adverse maternal conditions may impose selection on random variation in DNA methylation.

Human embryo at 8-cell stage. (C) Yorgos Nikas/Science Photo Library

Human embryo at 8-cell stage. (C) Yorgos Nikas/Science Photo Library

We used a mechanistic simulation model to illustrate how selection reduce DNA methylation variance at loci that influence implantation success. The prediction fits very well with empirical data from offspring conceived during the Dutch Hunger Winter, a famine at the end of World War II. This makes selection on stochastic epigenetic variation a reasonable explanation for the epigenetic signatures of prenatal exposure to adverse conditions.

This new hypothesis is not only of academic interest. Fetal programming implies that the behaviour or physiology of the mother causes the offspring phenotype to change. In contrast, a selective process does not bring new phenotypes into being, it changes the distribution of already existing variants. This difference may influence which preventive strategies and treatments that are most likely to be effective. That different mechanisms can be responsible for the same pattern is also relevant to society. As Sarah Richardson has pointed out, careless discussion of epigenetic research on how early life affects health across generations could be harmful.

Read More